The Worst Legacy of Boomers May Not Be Climate Change

Modern economies have contributed to a number of global phenomena that are problematic legacies. Pollution, climate change, resource depletion, and nuclear proliferation are well known. But the worst legacy of the boomer generation and the "silent" generation before it may be that they did not have enough children. See my prior post imploring women to have more babies.

International coverage of the birth rate problem in my native South Korea has been heavy for a few months. A top ten global economy, South Korea has defied international expectations for its rapid growth and development following Japanese occupation and a series of devastating wars. But in the foundational measure of birth rate, it now rings in at a world-worst 0.78 births per woman.

There is global fascination with where Korea finds itself, well short of the population sustaining birth rate of 2.1, and rife speculation as to why. Much of the chatter focuses on Koreans' lack of life satisfaction. As an OECD survey (2019-2021) reveals, South Korea ranks 36 of 38 reporting nations in Quality of Life. Among Koreans themselves, people talk about how few children they see these days. People don't have babies these days, they say in hushed tones.

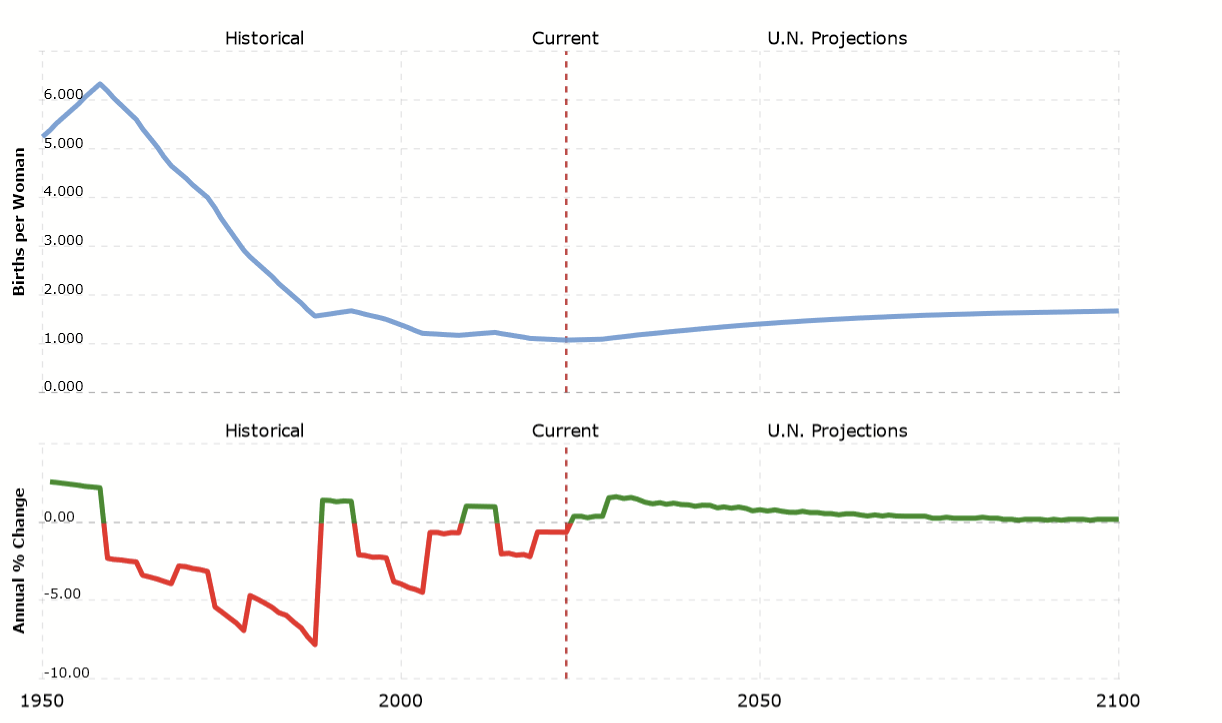

Obviously that is true. But people haven't been having babies in Korea for quite some time. Robust sustained populations are the bedrock for economic stability. And yet over the course of Korea's impressive rise, the birth rate fell just as rapidly, sowing the seeds of future trouble: from a peak of 6.3 in 1958, to a brief trough of 1.6 in 1988, to a gently declining undulation concluding in <1.

The crash happened in the 30 years between 1958 and 1988, when women went from having more than six children each, to having only three for every two women. The last time Korea had a population sustaining birth rate was in 1984.

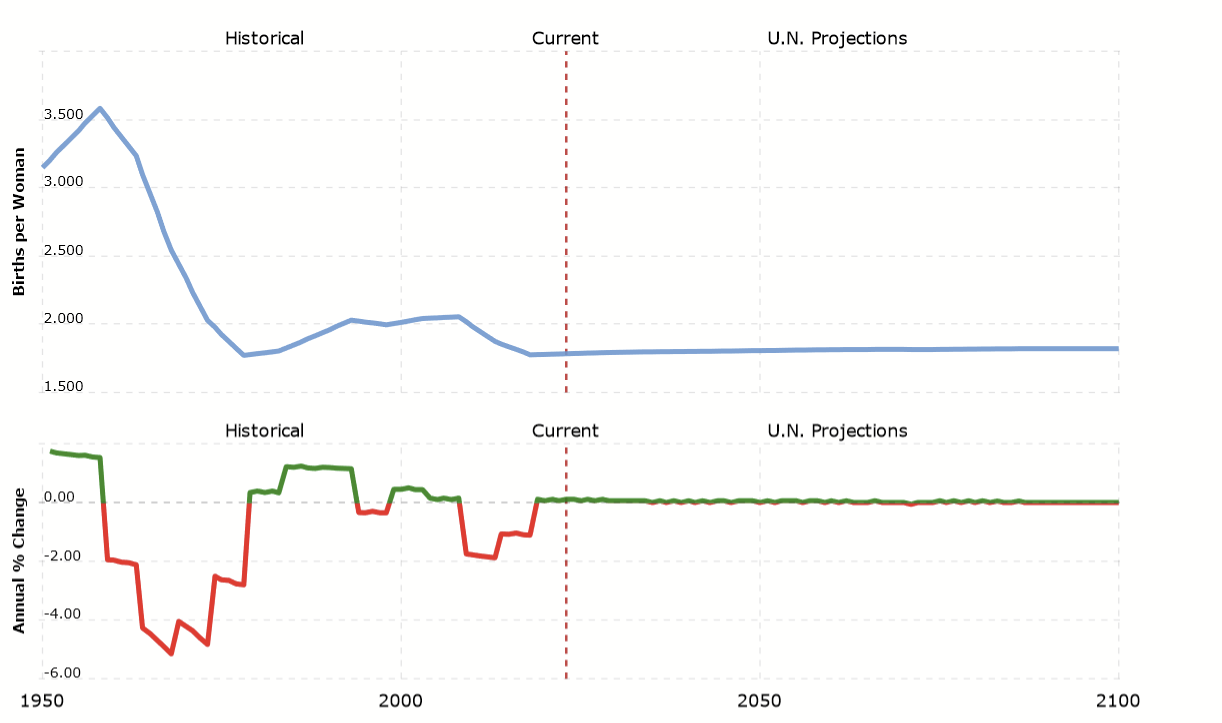

And Korea is not alone in having a crashing birth rate. The United States went from a peak of 3.6 in 1958, to a low of 1.8 in 1978, to a slight rise then back to 1.8. The United States is also not at a sustaining level of births.

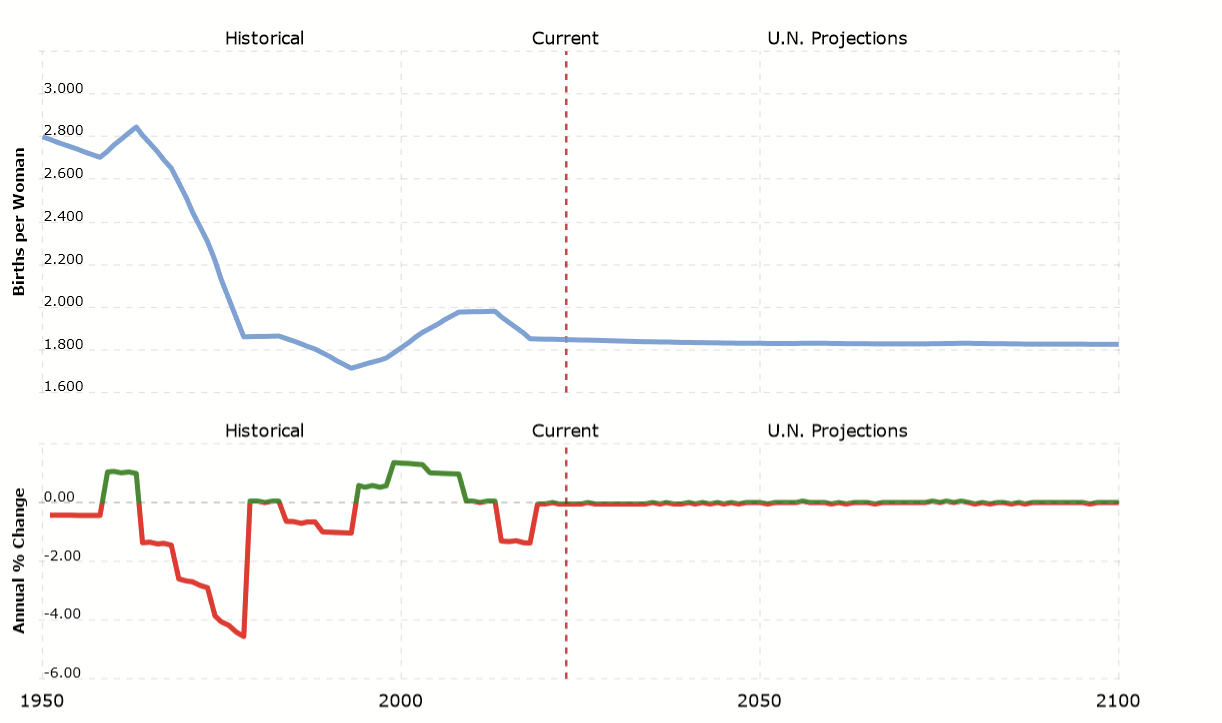

France peaked a bit later, at 2.8 in 1963. And it too crashed, to 1.7 in 1993, before rising slightly, then leveling out to about 1.8-1.9. It, too, along with every other country in the OECD, fails the population sustenance test.

When populations cannot sustain themselves, there is an inevitable conflict over the shrinking pie of national funds. France is currently in an uproar over President Macron's audacious maneuver to raise the national pension age from 62 to 64. Some 60% of the country supports the riots.

The United States, where the retirement age has been 65, and is easing upward to 70, also faces the reality of an aging average population, with Social Security posing an increasing burden on the national budget.

France and the United States are not alone. The reality for modern nations in this regard is bleak: there are way too many older people for the younger generations to support. Put another way: Today's pensioners needed to have had more children, on average, for the proverbial pie to continue increasing.

Unless modern economies inject their populations with immigration-fueled growth, particularly of skilled people of childbearing age, the Boomers and Silents, and everyone else, will be forced to have fewer and less social benefits. The difference among modern nations will be in how quickly this happens, and how severe the extent. Some societies will be better sharers of scarce resources than others.